The Loss of Sperry Chalet, 1913-2017

The outpouring of emotion at the loss of Sperry Chalet in Glacier National Park has been almost as overwhelming to us as the loss of the chalet itself. Or herself. Because she was 104 years old, and she had plenty of personality.

First things first: although the main structure, the gorgeous Italian-stonemason-wrought dormitory, has burned to the ground, we don’t believe it’s the loss of Sperry Chalet itself that has people pouring out their grief on the internets. The basin itself is magical. There is only one place in Glacier that you can fairly easily reach out and touch one of our last remaining glaciers, and it is just a short hike up from Sperry Chalet.

Glacier Guides and Montana Raft’s co-owner Denny Gignoux, camped at the Sperry Glacier in the mid 1970s with his father, who was working on a research project there.

Until that glacier melts, nothing can take away that experience. But the building itself, where generations have sat on the porches and watched the sun rise and set, and talked amongst their nearest and dearest, and made new friends, is certainly thought of by thousands as their backcountry home in Glacier.

Sperry Chalet offered the opportunity for nightly reflection amongst guests. Photo courtesy Sanford Stone.

Why? We think it’s because Sperry, more than any other place in the park, makes the idea of “wilderness” accessible to nearly all. Maybe your party is exceptionally fit and strong and came in the non-recommended but surely fabulous way, if you are very experienced in Glacier’s backcountry, through Floral Park, skirting Sperry Glacier itself and arriving famished and ready to tuck into turkey dinner. Maybe your party is adventurous and hearty and not afraid of two high mountain passes — Gunsight and Lincoln — and you hello-ed the mountain goats as the grand old girl came into view after 13.7 miles of incredible views on the Gunsight Trail. Maybe you slogged the 6.7 strenuous miles up from Lake McDonald on foot. Maybe you rode those 6 miles on a horse — and when you’re not used to them, riding horses ain’t always easy.

After an ACL injury, one of our own at Glacier Guides and Montana Raft was relieved to be able to ride a horse to Sperry, and reconnect with the backcountry she needed in her healing process. Photo credit: Tricia Pajak

That is part of Sperry’s magic — you don’t have to be skilled with a map to get up there or in particularly great shape, but it IS up there. Six and a half blissful miles removed from any trappings of civilization, without any cell service. If you got up there, you introduced yourself at dinner, signed the register, and then surely witnessed the hush that fell every evening without fail, as guest gathered on the porches, balconies, and stone walls. Friendships erupted easily but voices grew quiet, respecting fellow guests’ experience of watching the sun fade from the drainage. Conversations grew serious. Why don’t we do this more often? was something we heard frequently. The “this” is the disconnect from modern life. No screens, no distractions. Just a complete focus on the people, the moment that was always happening at Sperry as evening fell.

And that, we think, is the difference. No other place in the park affords that moment, even beloved Granite Park Chalet, which offers an equally amazing, but different, experience. You cook your own food at Granite, and to our chagrin you can get even an AT&T cell signal up there. The views at Granite are jaw dropping, and the camaraderie of the shared kitchen is something we think society needs more of. But it is a different — no less special, but different — experience. You can’t rent a horse to get up there, so it’s not as accessible as Sperry. Most of the trails leading to Granite are amongst Glacier’s most popular, and so the solitude level, at least until darkness falls, is different. We love Granite Park with all of our hearts — so much that we ran it in the late 1990s through the early 2000s — but this post is about Sperry’s singularity, so don’t take offense.

And so the loss of Sperry Chalet is felt keenly by the Glacier National Park community, which has always been a good one, and which this week has grieved and loved together. Will we rebuild? The smoke will have to clear before the Park Service can even begin to address that complicated question. For now, we thought we’d offer you a look at the history of the chalets. With the loss of Sperry, only Granite Park stands. What happened to the other 8 original Glacier National Park chalets?

The Original 9 Glacier National Park Chalets

St. Mary, Sun Point, Many Glacier, Two Medicine, Cut Bank, Gunsight Lake, Belton, Granite Park, and Sperry

Glacier National Park was created on May 11, 1910. The Going-to-the-Sun Road was dedicated in 1933. In the 23 years between the park’s creation and the road’s opening, many accommodations — chalets and lodges — were constructed, mostly about a day’s horseback ride apart from each other. Because Glacier was deemed “America’s Switzerland,” they largely shared a Swiss architectural theme, with gabled roofs, lots of oversized windows overlooking the mountains, balconies, ornate moldings, and exposed beams.

The 9 chalets were built between 1910-1915. Great Northern Railway built many of them, and also several of the first hotels during this time period, including the iconic Glacier Park Lodge in East Glacier, which was constructed from 1912-13, and the world famous Many Glacier Hotel, constructed from 1914-1915. Chalet complexes generally consisted of guest cabins, dining hall, an employee dormitory, and other outbuildings. The 9 original sites were Belton, St. Mary, Sun Point, Many Glacier, Two Medicine, Cut Bank, Gunsight Lake, Granite Park, and Sperry. As we reflect on the loss of Sperry Chalet, we thought it would be appropriate to offer a brief history of each of Glacier’s chalets.

St. Mary Chalets, 1912-1943

The St. Mary Chalets were constructed in 1912, but never really took off due to the popularity of the nearby Going-to-the-Sun Chalets. When the Going-to-the-Sun Road was constructed, it bypassed these chalets and today’s St. Mary village took off at the end of the Sun Road, several miles from the Chalets. Then the Great Depression hit, and then World War II. Lodging ceased in 1934. Hugh Black dismantled the St. Mary chalets in 1943, and likely used some of those materials in the construction of what is now St. Mary Lodge and Resort, which he founded.

Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, 1912-1948

What is now referred to as simply Sun Point began as Sun Camp and evolved by 1912 into the Going-to-the-Sun Chalet complex. By 1915, the gorgeous Sun Chalets, clinging to the cliffs of Sun Point, could house 200 lucky guests, and were extremely popular. Strangely, the opening of the Going-to-the-Sun Road lessened the popularity of the Sun Chalets, as they were now easily accessible by car — as opposed to by boat or horse — which apparently lessened their allure. Then came World War II, a lack of maintenance, and the blasting winter winds of the east side. Together, these events combined to put the Sun Chalets out of business in 1942 and dismantled in 1948.

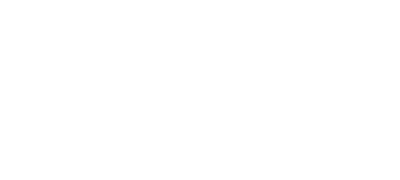

Many Glacier Chalets, 1913-1936

When you take a left towards the Many Glacier Hotel, you pass Many Glacier Chalets “H” and “I.” They are the only remaining structures of what was referred to as “Chalet City” or the “Lake McDermott Chalets,” as that was once the name of Swiftcurrent Lake. In 1913, Chalet City offered lodging for visitors to the Many Glacier valley. By the next year, they were offering support for the construction, and later operation, of the Many Glacier Hotel, which was completed in 1915. In 1936, most of Chalet City was destroyed by the famous Swiftcurrent Valley Fire that nearly burnt down the Hotel. Today, “H” and “I” house maintenance workers for the Hotel, including year round housing for the Many Glacier Hotel caretaker.

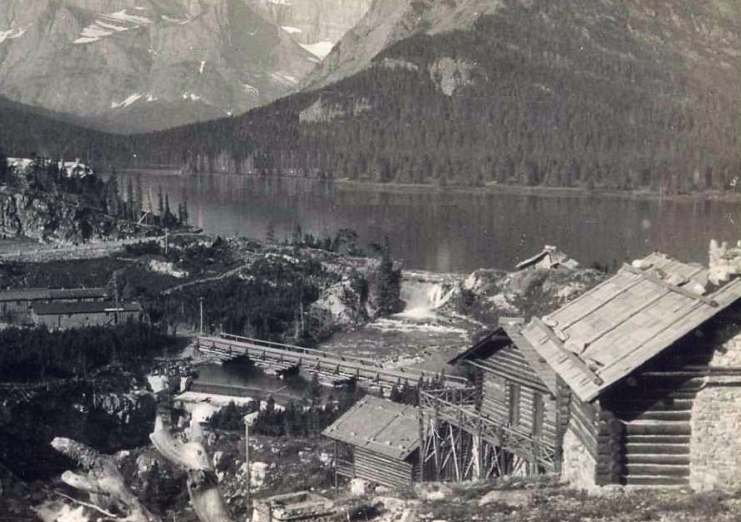

Cut Bank Chalets, 1913-1938

Originally known as the Cut Bank Teepee Camp in 1911, the Chalets were officially opened in 1913 and were an instant hit with anglers, as the fishing was then and is now amazing in the Cut Bank drainage. In 1915, a trail connecting Cut Bank to Two Medicine opened, and the area became even more popular. In fact, business was so good that as automobile traffic to the park increased in the 1920s, the Railway did not see a need to advertise the Cut Bank Chalets. But by 1933, the lack of advertising coupled with the Great Depression had closed the Chalets, and although they reopened briefly as a dude ranch in 1937, ultimately they did not recover. In 1938, Great Northern Railway asked the National Park Service for permission to close them, and after World War II, they were deconstructed in 1948-1949. Nothing remains.

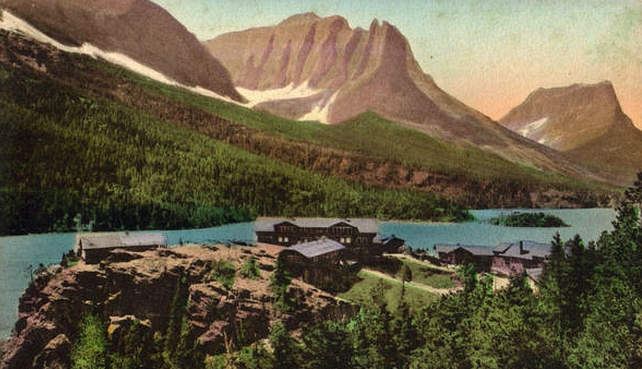

Gunsight Chalets, 1910-1916

This short lived Chalet complex was once amongst the most popular in the park, which is not surprising, as there is nothing about Gunsight Lake and Gunsight Pass that isn’t stunning. Construction began in 1910, the chalets opened in 1911, a hungry grizzly bear nearly destroyed the kitchen/dining chalet in the winter of 1913-1914, and a March avalanche destroyed the entirety of the Gunsight Chalets in 1916. Many visitors to the park think that the Gunsight Pass Shelter, a stone structure on Gunsight Pass, was once part of the chalet system, but they are incorrect. That Shelter was constructed in 1931 as a respite to travelers between Sperry and St. Mary. The Gunsight Chalets were located at the foot of Gunsight Lake, where a popular beach is located today.

Two Medicine Chalets

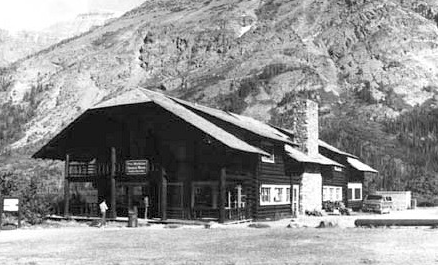

Two Medicine Camp Store, formerly part of the Two Medicine Chalets, Glacier National Park, circa 1985. NPS Photo.

The Great Northern Railway began construction on the Two Medicine Chalets in 1912. The accommodations were rustic, but the experience of waking up at the foot of Two Medicine Lake was considered transformative. (In 2017, we would agree.) In 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stayed at the Chalet and gave a radio address to the nation from Two Medicine. However, once more World War II took its toll, and lodging was discontinued in the 1940s. However, at around the same time, the kitchen/dining hall structure was transformed into the Two Medicine Camp Store. Today, the Two Medicine Camp Store is the only remaining structure from the Two Medicine Chalets. It continues to serve as the heart of the Two Medicine valley, remaining in service as a campstore and grab-n-go lunch spot.

The Belton Chalet

The Belton Chalet, located just outside the park in West Glacier, stands today as a living example for interpretation of the history of the railway and Glacier National Park. Back in 1910, it was constructed as the very first of the Great Northern Railway’s chalets, just across from the train station in present day West Glacier, then called Belton. Though successful at the start, World War II also took a heavy toll on the Belton, and it was sold after the war. For the next 50 years, it operated sporadically.

In 1997, record snowfall caved in roofs and buckled floors in some of the structures. Local residents Cas Still and Andy Baxter, inspired by the history of the chalet in support of Glacier National Park, decided to save the Belton. In 1999, their meticulous and authentic restoration of the Lodge to circa 1913 was received with great acclaim. The restored Belton Chalet has been honored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2000. At Glacier Guides and Montana Raft, we love to take advantage of the fine dining and cocktails offered nightly by our friends at Belton Chalet. Don’t miss this experience if you’re in the area!

Granite Park Chalet

The loss of Sperry Chalet leaves Granite Park as the last backcountry chalet standing in Glacier National Park. Granite Park Chalet was built in 1914 and 1915 by the Great Northern Railway to provide comfortable backcountry accommodations inside Glacier National Park. It was the last of the chalets built by the railroad. Granite Park is a stunning place, with sweeping views of Heaven’s Peak, the Livingstone Range, the Lake McDonald Valley, the Garden Wall, and the Logan Pass area. From every direction, the trails accessing Granite Park — from Waterton/50 Mountain, Logan Pass, the Loop, and Swiftcurrent — are gorgeous, and amongst the most popular in the park.

Granite is different from Sperry in many ways. While lodging is offered, guests share a large kitchen, each signing up for a time slot for cooking, as opposed to the three daily meals offered historically by the chalets, including Sperry. Guests must also haul their own water to Granite Park, for cooking and other purposes. Granite offers a few items for sale to guests and hikers passing through, and it can be a real treat on a hot summer’s day to buy an ice cold Coca-Cola and a candy bar to power you over Swiftcurrent Pass and down to the Many Glacier Hotel. Today, Granite Park Chalet is listed as a National Historic Landmark and is a treasured space in Glacier’s backcountry. We love it with all of our hearts, and look forward to helping guests experience Granite next summer, and hopefully all the summers to come.

Sperry Chalet

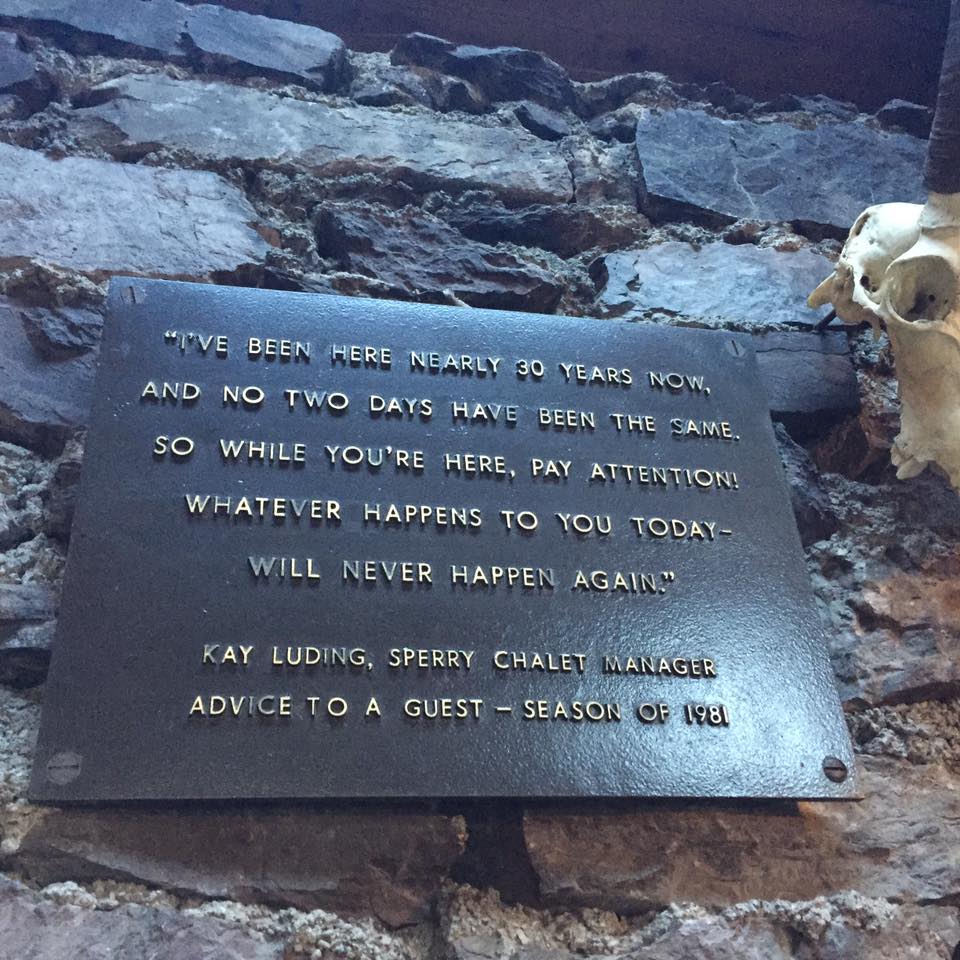

We almost lost Sperry Chalet for good in 1992, actually. You should know that Sperry’s construction began in 1912, by the Great Northern Railway, and was completed in 1913. It opened to guests in 1914 and was immediately one of the park’s most popular, and beloved, chalets. It then closed due to World War I in 1918. The Depression was hard on all the chalets, including Sperry. World War II closed it again from 1942-1944. But in 1954, the concession was transferred to the Luding family, who has largely operated it to date and who has played an incredible role in Sperry’s history. Kevin Warrington, the current operator, is a Luding.

Since 1954, Sperry has seen maintenance and improvements, but not much change. Throughout the years, Sperry has operated in much the same fashion as it did in 1914 — it has offered full service linen and dining at all times of operation, which is incredible when you think about the effort involved in providing those services 6.7 miles up a rocky trail and 28 miles from Columbia Falls, the closest town with large grocery stores. But more than that, Sperry has offered a return to quiet civility in these trying modern times.

One notable event in Sperry’s history is that in 1992, the Sierra Club threatened to sue the National Park Service over waste-water management at both Sperry and Granite Park chalets. The chalets were closed. The Philips family of Bozeman, a husband and wife team who met at the chalets, started a grass roots effort called “Save the Chalets.” This was aimed at working with the Park Service to re-open and maintain the chalets. Sperry reopened in 1996. In 2008, a new restroom facility was added. Then, on the night of August 31, 2017, the main structure of Sperry Chalet, the 17 room dormitory, burned to the ground in the Sprague Fire.

The loss of Sperry Chalet is hard to write about. Sperry has been a beloved haven in Glacier National Park, and we treasure every memory of falling asleep tucked into that beautiful cirque, listening to the mountain goats clomping around, always on guard. We know we are lucky to have so many of these memories.

Rebuilding Sperry Chalet

Will we rebuild Sperry Chalet? That is the question of the hour. Right now, we’re still in the midst of fire season, and there are other priorities within Glacier National Park. Stay with us for updates, and please share your Sperry memories with us. Those are irreplaceable in a way that stone walls are not. We know we have more memories to make in that very special basin.

Thank you, Sperry Chalet, for the experience.

Much of the information in this post was sourced from the Glacier Park Foundation and the National Park Lodging Architecture Society — their in-depth details on the chalets make for great reading.